Dhaka on a perilous path: Lax rules, weak oversight fuel unplanned expansion

Once regulated by strict rules, Dhaka's urban landscape has undergone a radical transformation over the last two decades, driven by the gradual relaxation of regulations, aggressive increases in floor area ratio (FAR), and weak enforcement of relevant laws.Near-unregulated vertical expansion has put immense pressure on utilities and infrastructure, worsened traffic congestion, and compromised fire safety in many areas of the city, according to experts.Urban planner Emdadul Islam, also a former c...

Once regulated by strict rules, Dhaka's urban landscape has undergone a radical transformation over the last two decades, driven by the gradual relaxation of regulations, aggressive increases in floor area ratio (FAR), and weak enforcement of relevant laws.

Near-unregulated vertical expansion has put immense pressure on utilities and infrastructure, worsened traffic congestion, and compromised fire safety in many areas of the city, according to experts.

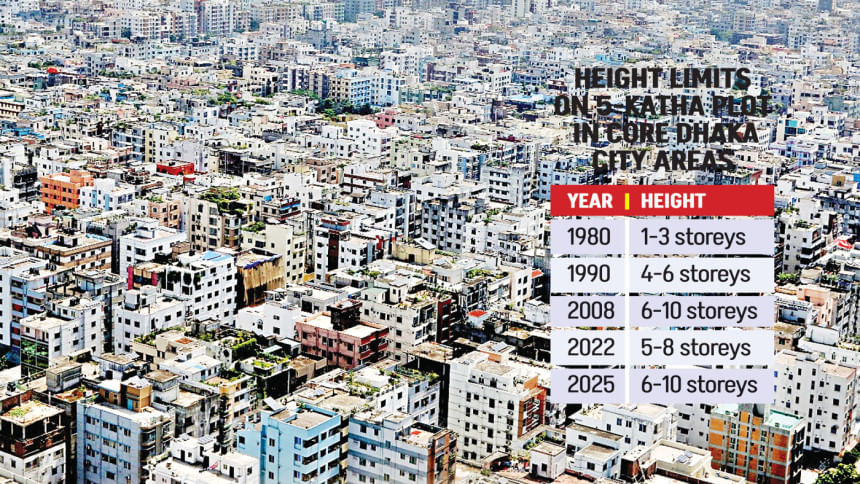

Urban planner Emdadul Islam, also a former chief engineer of Rajuk, recalled that the height of buildings in the neighbourhoods of Gulshan, Banani, and Dhanmondi was once capped at just three storeys.

In the 1980s, the rules were relaxed, allowing the construction of buildings up to six storeys.

Persuaded by developers, the government introduced FAR -- a limit on how much floor space is permitted on a piece of land -- in 2008 to encourage vertical growth and preserve open land. But in practice, the move made matters worse.

"The idea was to save horizontal space while meeting the housing demand… But in most cases, developers went for expansion both vertically and horizontally, wiping out open spaces," Emdadul explained.

Developers have often managed to bypass the rules altogether mainly due to minimal oversight by Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (Rajuk), entrusted with enforcing building regulations in the capital.

Recently, a three-member government body revised the Detailed Area Plan (DAP) 2022 and proposed raising FAR further in most core city areas -- a move that, according to urban planners, would allow developers to build even taller structures in the already overcrowded capital.

The proposal was approved in principle at a meeting of the advisory committee on DAP review, chaired by Land Adviser Ali Imam Majumdar on October 19.

Welcoming the development, Liakat Ali Bhuiyan, senior vice-president of Real Estate and Housing Association of Bangladesh (REHAB), said the move would help the sector come out of stagnation.

"Industries linked to the real estate sector will also benefit from this," he added.

PERILOUS PATH

Urban planner Adil Mohammed Khan, president of the Bangladesh Institute of Planners, said global planning norms are not followed in the case of Dhaka city.

Traditionally, plot-based development (small plots with strict height limits) coexisted with block-based colonies in Dhaka city, which included houses, schools, and open space. Dhaka initially followed the plot-based model, capping the height at two-and-a-half storeys that ensured airflow and sunlight.

But all this changed with the formulation of the 2006 Building Construction Rules after developers promoted FAR as a way to meet the housing demand.

They promised to leave more open space while constructing structures. But in practice, neighbourhoods have become mismatched: four-storey houses are seen beside 10-storey high-rises, he said.

"Even in developed countries, height limits preserve neighbourhood character… High-rises belong in business districts, not alleys in residential areas," Adil pointed out.

In most countries, FAR rarely exceeds 2 in residential areas, meaning that the total floor area is twice the size of the land, he said.

But the 2008 rules allowed FAR between 3.5 and 6.5, depending on road width. This enabled 10-storey buildings beside narrow roads and 20-storey high-rises beside main roads. Now, 14-storey towers rise from alleys barely wide enough for rickshaws.

Adil said the authorities are approving the construction of high-rises in congested neighbourhoods with lanes too narrow for fire trucks. "Some roads are too narrow for two cars to pass, yet developers want towers there. It's chaos."

Many high-rises are unreachable by fire trucks or ladders. Developers who pledged open spaces in return for higher FAR often build structures without leaving adequate open space, he said.

Mohammad Fazle Reza Sumon, former president of Bangladesh Institute of Planners, said that with higher FAR, the population of urban areas could go beyond the designed capacity, putting unbearable strain on utilities and infrastructure.

For example, Purbachal was originally designed for 10 lakh residents, but was later revised to accommodate 15 lakh.

With higher FAR, its population could soar to 60 lakh, putting utilities and infrastructure under severe strain. This is precisely why areas like Mohammadpur and Dhanmondi are already struggling.

An increase in the number of residents beyond capacity will lead to a surge in vehicles, worsening traffic congestion in the city, he noted.

Another negative impact of unplanned urban expansion is the loss of daylight.

In small plots of 4-5 kathas, residents of two or three-storey buildings have access to at least two hours of natural light daily. But if high-rises are built on adjacent plots, they block all sunlight to neighbouring homes, Sumon said.

This is why buildings are limited to 3-4 storeys in most residential neighbourhoods in India, Pakistan, South Korea, the US or Australia, he said.

DETAILED AREA PLAN

The 2022 DAP sought to introduce area-based FAR, depending on road width and civic facilities. Later, FAR was raised for almost all areas in the capital following demands from developers.

Though the approved plan capped FAR between 2 and 4.5, the limits were raised in many areas in September 2023. FAR is now between 5 and 5.5 for residential areas in Gulshan, Banani, and Dhanmondi.

"When it comes to planning, FAR 5 or 5.5 is unthinkable for residential plots… On narrow roads, it should not exceed 2.5 -- at most 3. Raising it to 5.5 means disaster for neighbourhoods," said Adil.

Mohammad Ashraful Islam, project director of DAP and Rajuk's chief town planner, said a three-member subcommittee, led by Housing and Public Works Adviser Adilur Rahman Khan, revised DAP 2022 and prepared a proposal after discussions with all stakeholders.

He said the proposal, approved in principle by the advisory committee recently, will be sent to the law ministry soon for vetting.

According to the proposal, FAR has been raised in most core city areas, including Kazipara, Shewrapara, Jatrabari and Badda, while it has been slightly reduced in a few areas, including Dhanmondi and Gulshan.

Ashraful said flood flow zones will be unified under a single category to protect them from encroachment. Development or construction on agricultural land will be prohibited, with the exception of projects of national interest.

It will be mandatory for a developer to install a Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) if the plot size is five katha (3,600sq ft) or larger, he added.