Persons with disability protected on paper, excluded in reality

At just 21, Jyoti Hossain from Jhikargachha, Jashore, is fighting not her disability but rather a system that refuses to include her.Confined to a wheelchair since age four after a spinal cord injury, Jyoti excelled in school, earning an A+ in both SSC and HSC exams. Last year, she fulfilled her dream of studying Physics at Government MM College, Jashore.But barriers soon closed in. With no accessible transport, she spends Tk 1,400 a day on private cars, and the college's third-floor physics lab...

At just 21, Jyoti Hossain from Jhikargachha, Jashore, is fighting not her disability but rather a system that refuses to include her.

Confined to a wheelchair since age four after a spinal cord injury, Jyoti excelled in school, earning an A+ in both SSC and HSC exams. Last year, she fulfilled her dream of studying Physics at Government MM College, Jashore.

But barriers soon closed in. With no accessible transport, she spends Tk 1,400 a day on private cars, and the college's third-floor physics lab -- without a lift -- remains out of reach.

After a year of struggling, her teachers advised her to abandon Physics and switch to the degree pass curse, saying practical work would soon become "too difficult" for her.

"Physics is my favourite subject. Why should I switch?" Jyoti said. "This disability is not my fault, so why should I give up my dream?"

Her story exposes the stark gap between law and reality in Bangladesh.

The Rights and Protection of Persons with Disabilities Act 2013 and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) guarantee equal access to education and infrastructure.

Yet inaccessible campuses and systemic neglect continue to hold back students like Jyoti. Bangladesh ratified the UNCRPD in 2007 and its Optional Protocol in 2008.

The 2013 Act incorporated the convention's principles into national law, and the 2019 National Action Plan on Disability outlined short, medium, and long-term goals for 35 ministries across 18 thematic areas.

Still, experts say enforcement remains weak, and policies rarely translate into practice.

Bangladesh enforces the 2013 Act through five disability rights committees -- from local to national -- covering education, health, employment, and rights. They operate under the National Disability Development Foundation (NDDF) under the Ministry of Social Welfare.

By law, these committees must meet regularly, but experts say they rarely do, leaving monitoring extremely weak.

Dr Nafeesur Rahman, a disability development expert, said deputy commissioners chair too many committees to prioritise them. "Despite legal powers, these committees remain largely ineffective," he said.

"Most district committees fail to submit reports, and the NDDF's managing director, who serves as member secretary of the national committees, lacks manpower and resources to analyse them," he added.

Ashrafunnahar Mishti, executive director of the Women with Disabilities Development Foundation, said rare disabilities often go unrecognised and disability cards cannot be issued because committees are inactive.

She said employment discrimination is severe, with recruitment of visually impaired teachers in government schools largely halted since 2014.

"Even worse, remarks like 'Not good-looking, cannot teach' have been reported during interviews -- despite court rulings in favour of 204 candidates with disabilities," she said. "Even at the NDDF, only two persons with disabilities are employed."

Md Jahangir Alam, senior coordinator at the Centre for Disability and Development, called for structural reform: "The social welfare and public administration ministries must make the committees functional. NDDF must be restructured with adequate staff and resources."

Dr Nafeesur said financial constraints are a major barrier: "The National Action Plan has no dedicated budget, and ministries have not integrated disability inclusion into their mandates, since all disability-related issues fall under Social Welfare."

UNCRPD implementation faces similar challenges.

A National Monitoring Committee and 47 ministry focal points were established to coordinate inclusive development, but the committee -- never empowered under the Paris Principles -- has been inactive since 2017.

Bangladesh must report to the UN every four years but has submitted only one report, in 2017.

During the 2022 UN review, the Bangladesh delegation -- led by foreign ministry officials, not social welfare -- struggled to defend the report, as they were not directly involved with disability issues.

"It exaggerated the situation and contradicted information given by organisations of persons with disabilities," said Mishti, one of the delegates.

"As a result, state representatives were furious, and I was even threatened for exposing the real situation," she alleged.

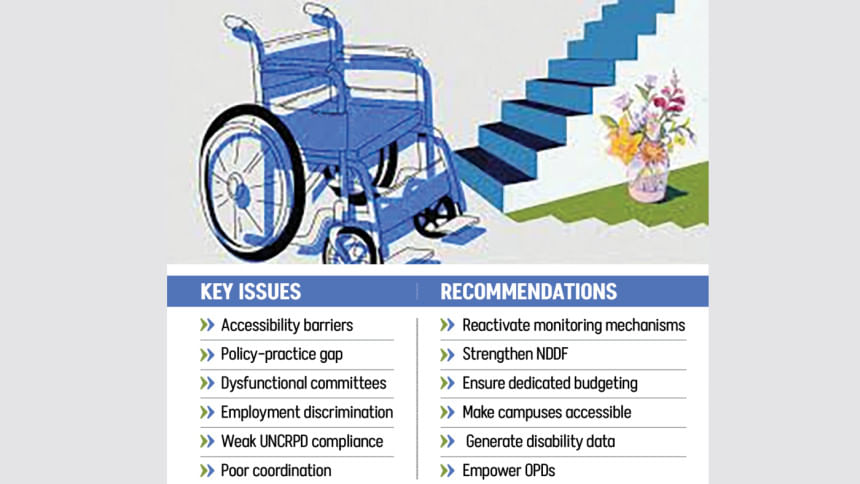

In October 2022, the UNCRPD Committee issued Concluding Observations, identifying serious gaps -- inadequate data, stigma, poor accessibility, weak oversight, limited access to justice, and the absence of a Paris Principles–aligned monitoring mechanism.

It recommended aligning laws with the UNCRPD, strengthening monitoring and accessibility, combating discrimination, improving access to justice, promoting inclusive livelihoods, collecting disaggregated disability data, and supporting OPDs to participate meaningfully in policymaking.

Bangladesh was asked to submit its next reports by December 2029, but progress has been minimal.

NDDF Managing Director Bijoy Krishna Debnath acknowledged severe capacity constraints. "I'm holding additional responsibilities, so I only handle urgent tasks. Permanent staff shortages make it impossible to keep committees fully functional," he said.

He also cited budget pressures. "The lump-sum allocation from the finance ministry has to cover 74 schools, 103 service centres, rent, utilities, and assistive devices."

On UNCRPD implementation, he said, "The law is not fully implemented yet, but it will happen gradually, perhaps once a dedicated disability budget is introduced."

Monsur Ahmed Chowdhury, president of Disability Rights Watch and a former UNCRPD Committee member, stressed the need for urgent institutional reform.

"The National Monitoring Committee must be reactivated," he said. "The Cabinet Division should empower it under the Paris Principles, and all ministries must reassign joint secretary-level focal points. Immediate action is needed to implement the UN committee's recommendations."

Looking ahead, Dr Susan Vize, Unesco representative to Bangladesh, said effective implementation of disability rights laws and UNCRPD obligations "requires a shift to accountability-driven mechanisms."

She stressed the need for an independent monitoring body, meaningful involvement of organisations of persons with disabilities, and disability inclusion across ministries and budgets.

Beyond laws and policies, changing mindsets remains a major challenge, she added.

Dr Vize stressed that shifting societal perceptions requires a multi-faceted approach, combining visibility, participation, education, and accountability, so persons with disabilities are recognised as full-rights citizens.