Climate finance fuels ‘debt trap’

Ten years after the Paris Agreement vowed climate justice for vulnerable nations, global leaders have gathered in the Brazilian city of Belém for COP30. But as negotiations unfold, Bangladesh, one of the world's least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, finds itself sinking deeper into climate debt.The inaugural Climate Debt Risk Index, published by Dhaka-based think tank Change Initiative, has placed Bangladesh in the "high risk" debt-trap category with a score of 65.37 out of 100, foreca...

Ten years after the Paris Agreement vowed climate justice for vulnerable nations, global leaders have gathered in the Brazilian city of Belém for COP30. But as negotiations unfold, Bangladesh, one of the world's least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, finds itself sinking deeper into climate debt.

The inaugural Climate Debt Risk Index, published by Dhaka-based think tank Change Initiative, has placed Bangladesh in the "high risk" debt-trap category with a score of 65.37 out of 100, forecasting a continued upward trajectory to 65.63 by 2031.

The report, which analysed debt scenarios across 55 countries, says that global climate finance has turned into an instrument of financial burden, straying far from the grant-based, justice-driven commitments made in the Copenhagen and Paris accords.

"Bangladesh enters COP30 carrying one of the world's heaviest climate-debt burdens, not because it over-borrowed, but because the global climate finance system keeps forcing the most vulnerable to pay for survival," said M Zakir Hossain Khan, managing director and chief executive of Change Initiative.

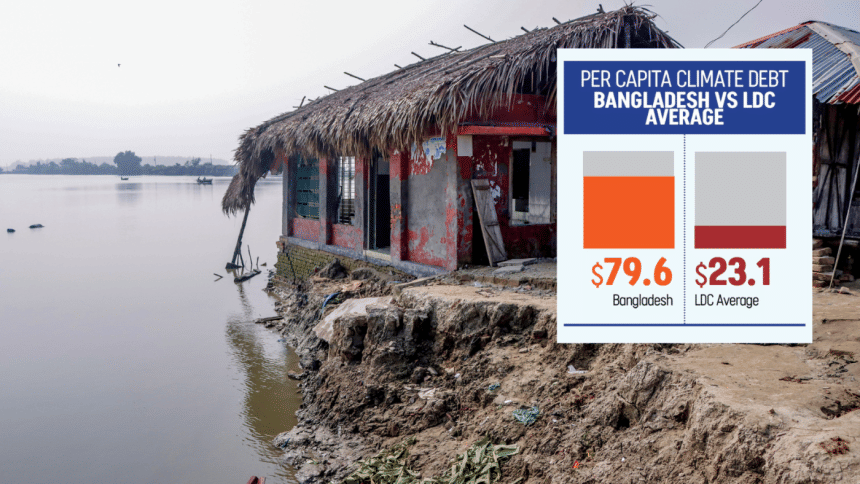

The financial burden on Bangladeshi citizens is starkly disproportionate. According to the study, Bangladesh's cumulative climate-related borrowing from 2002 to 2023 has created a per capita debt burden of $79.61, about 3.5 times higher than the average for Least Developed Countries (LDCs), which stands at $23.12.

The country is now compelled to borrow $29.52 for every tonne of carbon emitted, just below the LDC average of $30.49.

Overall, for every $1 Bangladesh receives as grants, it gets $2.70 in loans, placing it among nations facing the steepest climate-debt risks. Across LDCs, over 70 percent of climate finance arrives as loans.

"At COP30, Bangladesh will urge the world to replace loans with justice, through 100 percent grant-based adaptation finance. This is not charity; it's moral accounting," Khan said, citing an advisory from the International Court of Justice.

The period spanning 2009 to 2022 witnessed a substantial and worrying acceleration in Bangladesh's climate-related liabilities.

In this period, Bangladesh accrued $3.4 billion in climate-related loans, data cited in the research showed, highlighting the country's growing dependence on external borrowing for adaptation and resilience.

Total external debt service costs for LDCs surged to $50 billion in 2021 from $31 billion in 2020, with climate loans rising faster than repayment capacity, according to a report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). For over a decade, LDCs like Bangladesh have consistently received more climate loans than grants.

In response to mounting risks, Bangladesh formulated its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) in 2022, identifying 113 high-priority interventions across eight sectors, including water resources, agriculture, and urban resilience.

Experts estimate the plan will require $230 billion, or about $8 billion annually, from 2023 to 2050.

But historical data reveal an enormous financing gap.

From 2002 to 2023, Bangladesh secured only $1.41 billion in adaptation funds, less than 1 percent of its projected needs.

Similarly, while the country needs $3.23 billion annually for mitigation under its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), it has allocated just $360 million a year between 2020 and 2024, only 11 percent of the requirement.

MISATTRIBUTION

The report also flags widespread misclassification of projects, with around $880 million, nearly 19 percent of all climate funds, wrongly recorded as climate finance between 2002 and 2023.

These projects carry a staggering loan-to-grant ratio of 28.8, artificially inflating national debt while diverting money from genuine resilience efforts.

If the new global climate finance goal of $1.3 trillion for LDCs fails to uphold principles of fairness and equity, the report warns, "every cyclone that hits the coast will add not just loss of life, but another line of debt".

The World Bank estimates that Bangladesh experiences an annual economic loss of about $1 billion from average tropical cyclones. By 2050, one-third of agricultural GDP may be lost due to climate variability and extreme events.

"COP30 must end this cycle by linking finance to rights, resilience, and regeneration," Khan said.