Barind’s rice bowl is running dry

As world leaders prepare to convene at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, to chart a global path on carbon reduction, climate adaptation, and finance, the effects of inaction are already hitting home. In northern Bangladesh's Rajshahi region, marginal farmers are battling erratic monsoon patterns and rising temperatures -- climate woes that are crippling crops and leaving futures uncertain. Pinaki Roy reports from the ground.Pointing to the cracks in his Aman paddy field, Kongres Tudu, a Santal farmer of R...

As world leaders prepare to convene at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, to chart a global path on carbon reduction, climate adaptation, and finance, the effects of inaction are already hitting home. In northern Bangladesh's Rajshahi region, marginal farmers are battling erratic monsoon patterns and rising temperatures -- climate woes that are crippling crops and leaving futures uncertain. Pinaki Roy reports from the ground.

Pointing to the cracks in his Aman paddy field, Kongres Tudu, a Santal farmer of Rajshahi's Godagari upazila, said the soil dried out and fractured after just a week without irrigation.

"If I cannot irrigate my field within a couple of days, most of the crops will turn sterile, bearing no grain at all," Tudu said, adding that he couldn't arrange money in the first week of October to buy water from a deep tubewell operator for irrigation.

Though it rained a bit more this year than the last, the field still needs irrigation every week, said the 55-year-old farmer.

Narrating the financial strains on farmers in his area, he said that a Santal farmer from nearby Barshapara village became so depressed by his inability to irrigate his paddy field that he tried to take his own life by drinking pesticide in 2023.

In the previous year, two Santal farmers -- Avinath Mardi and Rabi Mardi from a nearby village -- died by suicide after a tubewell operator allegedly refused them water they were entitled to, according to their family members.

Md Selim Mia, a farmer from Tanore upazila, said their tubewell, which is 40 feet deep, can no longer pump out water.

"Now we have to install a deep tubewell. We all are heavily dependent on groundwater extraction here," he added.

Both Tanore and Godagari upazilas fall in the water-stressed Barind region, known as the rice bowl of Bangladesh.

The region was comparatively a barren area even in the mid-1980s, with very limited sources of surface water. In the 1990s, the Barind Multipurpose Development Authority (BMDA) introduced deep tubewells, enabling farmers to cultivate three crops a year.

The region now faces a major crisis with groundwater levels declining fast and temperatures rising rapidly amid a change in rainfall patterns.

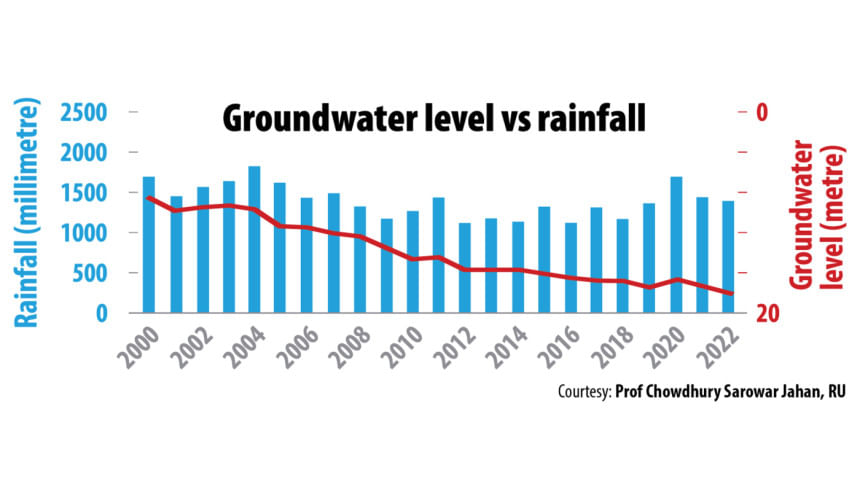

"Climate change is a silent killer here. In Rajshahi region, the average rainfall is 1,235mm against the nationwide average of 2,000mm," said Chowdhury Sarowar, who has been studying the region's climate for over a decade.

"If you visit the region, you'll see lots of crop fields and many fruit orchards. It's hard to understand the drought-like situation here at first glance, as all these crops and fruits are grown at the cost of groundwater," said Sarowar, a professor of geology and mining at Rajshahi University.

Crops like Aman, which are traditionally rainfed, now require frequent irrigation, he added.

Like the two upazilas in Rajshahi, Sapahar in Naogaon is also hit by an acute water shortage.

Imdadul Haque, a farmer of the upazila, said, "It doesn't rain here like before. Groundwater is declining. Even deep tubewells sometimes fail to draw water."

"If you dig deeper, you get red clay most of the time. There is no water," he said.

Only a decade ago, groundwater could be found by digging around 30 feet. Now, one may have to dig as deep as 80 feet to get water, said the farmer.

Amid a steady decline in groundwater level, the government in August declared 50 unions in 26 upazilas of four districts as severely water-stressed. Of them, 47 are in Rajshahi, Chapainawabganj, and Naogaon, and three are in Chattogram's Patiya upazila.

The government is now preparing guidelines to limit the use of water in these areas.

CHANGES IN RAINFALL PATTERNS

According to a study by Bangladesh Meteorological Department, rainfall in the northern region is steadily declining.

Rajshahi division is seeing a drop in rainfall by 54mm per decade, said the study, published last year, which analysed Bangladesh's rainfall data from 1980 to 2023.

"Changes in rainfall patterns in the region mean monsoon rains are decreasing while torrential rains are increasing in the post-monsoon period," said Bazlur Rashid, a meteorologist from BMD.

Geologists said the Barind region, which covers around 7,770 square kilometres, is mostly composed of hard clay that cannot hold rainwater. The region also differs from the surrounding floodplains.

"In the region, no sand layers capable of retaining groundwater are found between 200 and 800 feet. Only hard clay exists throughout," said Anwar Zahid, former director of Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB).

"The groundwater level in the northern region has fallen up to 80 metres over the last 50 years," said Anwar, who led a study by BWDB in 2022.

He further said that the decline in rainfall is hampering not only groundwater recharge but also causing surface water bodies to dry up.

The study, which analysed 50 years of data (from 1970 to 2020) from 465 shallow groundwater observation wells, found that the groundwater table has been in decline in at least 38 districts due to excessive extraction during the dry season.

RISING TEMPERATURE AND ITS IMPACT

The drop in rainfall has resulted in a steady rise in temperature, triggering a surge in pest populations and disrupting pollination, said agriculture experts.

Both maximum and minimum temperatures increased in all eight divisions of the country during last year's monsoon season, said the BMD study, noting that drought-prone Rajshahi recorded the steepest rise in temperature -- 0.5 degrees Celsius per decade.

Regarding its impact on agriculture, Sharmin Sultana, additional deputy director (crops) of the Department of Agricultural Extension in Rajshahi, said rising temperatures are fuelling pest outbreaks, which may affect agricultural productivity.

"With the rise in temperature, infestations of a pest, locally known as the brown grasshopper, have become more frequent. To check them, farmers need to use pesticides, which in turn pose risks to food safety," she explained.

Sharmin further said the temperature starts rising in Rajshahi in March, and when the average exceeds 35 degrees Celsius, it severely disrupts pollination of Boro, the main crop in the Barind region.

"When the temperature rises, the groundwater level drops, making irrigation increasingly difficult for farmers in the region. Moreover, many farmers suffer heatstroke while harvesting paddy or working in fields during the extremely hot months, especially in May," she added.

[Our Rajshahi correspondent Shohanur Rahman Rafi contributed to this report]